Automated Market Maker Simply Explained | OpenPad DeFi

Automated market makers are, to put it simply, autonomous trading systems that eliminate the necessity for centralized exchanges and associated market-making procedures.

TL;DR:

Market maker is an individual or firm providing continuous liquidity to trading partners so they can execute trades without worrying about constantly finding counter parties.

AMMs are computer networks designed to replicate the actions of market makers in order to address some of the problems created by human market makers at a much reduced cost.

By definition, AMMs are the protocols underlying decentralized exchanges (DEX) set to enable automated, unstoppable trading using algorithms to price assets in liquidity pools.

There’s a saying that on wall street, people use acronyms and abbreviations to build this false sense of accomplishment by making what they are doing sound more challenging than it actually is. We feel like the same sentiment carries over in the crypto space. Alright, today we will be taking on a vital concept within the context of DeFi; we know that in the crypto space, definitions and abbreviations can become daunting, so let’s take another big one off the list today with Automated Market Makers (AMMs). There is this subreddit we love, which is called “explain it like I’m five,” so let’s take something that has been way too needlessly overcomplicated and break it down to bits. Let’s start out with the definition of “Market Making,” for starters.

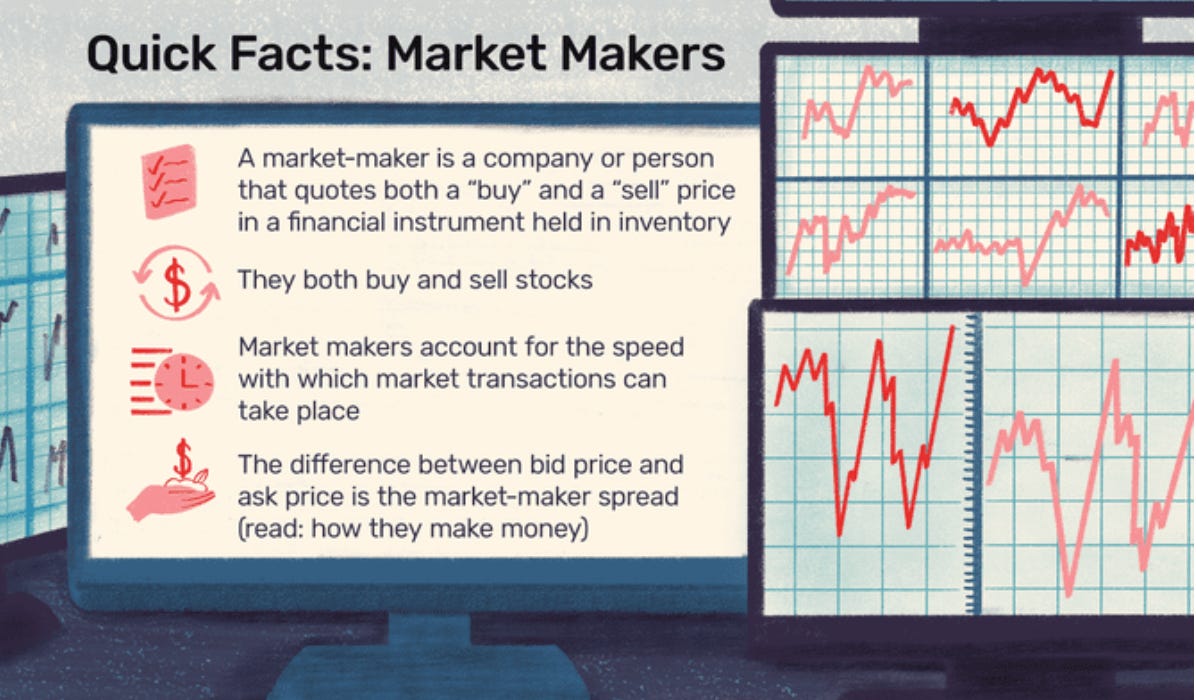

What is a market maker?

A centralized exchange oversees the operations of traders and provides an automated system that ensures trading orders are matched accordingly. In other words, when Trader A decides to buy 1 BTC at $24,000, the exchange ensures that it finds a Trader B that is willing to sell 1 BTC at Trader A’s preferred exchange rate. As such, the centralized exchange is more or less the middleman between Trader A and Trader B. Its job is to make the process as seamless as possible and match users’ buy and sell orders in record time.

So, what happens if the exchange cannot find suitable matches for buy and sell orders instantaneously?

In such a scenario, we say that the liquidity of the assets in question is low.

Liquidity, in terms of trading, refers to how easily an asset can be bought and sold. High liquidity suggests the market is active and there are lots of traders buying and selling a particular asset. Conversely, low liquidity means there is less activity and it is harder to buy and sell an asset.

When liquidity is low, slippages tend to occur. In other words, the price of an asset at the point of executing a trade shifts considerably before the trade is completed. This often occurs in volatile terrains like the crypto market. Hence, exchanges must ensure that transactions are executed instantaneously to reduce price slippages.

To achieve a fluid trading system, centralized exchanges rely on professional traders or financial institutions to provide liquidity for trading pairs. These entities create multiple bid-ask orders to match the orders of retail traders. With this, the exchange can ensure that counterparties are always available for all trades. In this system, the liquidity providers take up the role of market makers. In other words, market-making embodies the processes required to provide liquidity for trading pairs.

Market makers are compensated for the risk of holding assets because a security's value may decline between its purchase and sale to another buyer.

In the 1990s, human market makers were in charge of delivering bids and asking based on market depth and quoting market depth. Unfortunately, humans opened up the doors for a great deal of market manipulation - not to mention frequent latency and slippages in the Market’s price discovery mechanisms. The system had flaws.

Which is where AMMs come into the picture.

What is an automated market maker?

Now that we have got that out of the way, let’s proceed. AMMs are computer networks designed to replicate the actions of market makers in order to address some of the problems created by human market makers at a much-reduced cost. By definition, AMMs are the protocols underlying decentralized exchanges (DEX) set to enable automated, unstoppable trading using algorithms to price assets in liquidity pools. This allows users to trade crypto with other participants in the pool instead of traditional buyers and sellers. AMMs replace traditional order books with user-sourced liquidity pools and non-custodial smart contracts to handle and execute trades.

Difference between CEX and DEX

Unlike centralized exchanges, DEXs look to eradicate all intermediate processes involved in crypto trading. They do not support order matching systems or custodial infrastructures (where the exchange holds all the wallet private keys.) As such, DEXs promote autonomy such that users can initiate trades directly from non-custodial wallets (wallets where the individual controls the private key.)

Also, DEXs replace order matching systems and order books with autonomous protocols called AMMs. These protocols use smart contracts – self-executing computer programs – to define the price of digital assets and provide liquidity. Here, the protocol pools liquidity into smart contracts. In essence, users are not technically trading against counterparties – instead, they are trading against the liquidity locked inside smart contracts. These smart contracts are often called liquidity pools.

Notably, only high-net-worth individuals or companies can assume the role of liquidity providers in traditional exchanges. As for AMMs, any entity can become a liquidity provider as long as it meets the requirements hardcoded into the smart contract.

The most famous example of a DEX utilizing AMMs is Uniswap; other notable examples include Kyber and Curve.

That’s Cool, but How Does it Work?

The user-friendly tools and trading capabilities of traditional exchanges continue to be well-known. Decentralized exchanges, however, serve fundamentally different purposes than classic order books. The AMM model operates on the principle of liquidity pools, which, as mentioned, makes trading possible via an algorithm that determines token prices based on the ratio of tokens supplied at a given time. Providers of liquidity supply liquidity in the form of digital assets to pools in exchange for trading fees based on the amount of liquidity they provide.

Mechanisms tend to differ between exchanges, but generally, the process is similar. When users trade on the AMM, the smart contract is programmed to automatically send these tokens to corresponding liquidity pools and exchange them for parallel tokens.

Since each pool typically consists of a pair of tokens, an appropriate ratio can be calculated using specific formulas that determine how it’s structured.

At the very core, AMMs rely on a mathematical formula to evaluate the assets pooled in their protocol. Get your calculator ready!

The formula can vary with each protocol, but the most common one used by already established protocols is x*y=k, where x stands for the number of a certain token deposited in the liquidity pool; stands for the number of tokens of another coin in that same pool, and k stands for the constant and balanced price.

The formula above essentially means that if you want to withdraw a certain amount of token x, you must also deposit token y in equal amounts to prevent imbalance.

Let’s put things into perspective with an example

There are two essential things to know first about AMMs:

Trading pairs you would normally find on a centralized exchange exist as individual “liquidity pools” in AMMs. For example, if you wanted to trade ether for tether, you would need to find an ETH/USDT liquidity pool.

Instead of using dedicated market makers, anyone can provide liquidity to these pools by depositing both assets represented in the pool. For example, if you wanted to become a liquidity provider for an ETH/USDT pool, you’d need to deposit a certain predetermined ratio of ETH and USDT.

To make sure the ratio of assets in liquidity pools remains as balanced as possible and to eliminate discrepancies in the pricing of pooled assets, AMMs use preset mathematical equations. For example, Uniswap and many other DeFi exchange protocols use the simple x*y=k equation we mentioned above to set the mathematical relationship between the particular assets held in the liquidity pools.

Here, x represents the value of Asset A, y denotes the value of Asset B, while k is a constant.

In essence, the liquidity pools of Uniswap always maintain a state whereby the multiplication of the price of Asset A and the price of B always equals the same number.

To understand how this works, let us use an ETH/USDT liquidity pool as a case study. When ETH is purchased by traders, they add USDT to the pool and remove ETH from it. This causes the amount of ETH in the pool to fall, which, in turn, causes the price of ETH to increase to fulfill the balancing effect of x*y=k. In contrast, because more USDT has been added to the pool, the price of USDT decreases. When USDT is purchased, the reverse is the case – the price of ETH falls in the pool while the price of USDT rises.

When large orders are placed in AMMs and a sizable amount of a token is removed or added to a pool, it can cause notable discrepancies to appear between the asset’s price in the pool and its market price (the price it’s trading at across multiple centralized exchanges.) For example, the market price of ETH might be $3,000 but in a pool, it might be $2,850 because someone added a lot of ETH to a pool in order to remove another token.

This means ETH would be trading at a discount in the pool, creating an arbitrage opportunity. Arbitrage trading is the strategy of finding differences between the price of an asset on multiple exchanges, buying it on the platform where it’s slightly cheaper and selling it on the platform where it’s slightly higher.

For AMMs, arbitrage traders are financially incentivized to find assets that are trading at discounts in liquidity pools and buy them up until the asset’s price returns in line with its market price.

Pros and Cons of Automated Market Maker

When the existence of AMMs came to light, the disadvantages of traditional market makers – time inefficiency and cost, among others – were revealed.

However, AMM crypto exchanges also have their fair share of drawbacks in their design. The most common risk involving the AMM DeFi model is the possibility that liquidity providers in the pool may experience impermanent loss when there is a sudden rise in the market price of a major asset like ETH, causing a price reserve imbalance.

DeFi is a paradigm shifting innovation, and the more we get into it, the more we become fascinated by it. Today we covered another major player within this context. Some may say that the age-old man vs. machine theme can be sniffed out here and man should prevail, but we know that at least the machine will be just/fair; it won’t be seeking its profit, nor can it be corrupted. We have barely scratched the surface; let’s see where the rabbit hole takes us.

Resources to Learn & Invest with OpenPad

🕸 Home: openpad.app

📖 Docs: docs.openpad.app

🧢 Twitter: twitter.com/OpenPadCitizens

📒 Web3 Newsletter: openpad.substack.com

🔗 Official Links: linktr.ee/openpad